States around the country are redrawing their Congressional maps in a once a decade process called redistricting, and it will impact which political party controls both the United States House of Representatives and State Houses for the next ten years. Adjusting the maps is a constitutional requirement designed to help reflect population changes over time.

Every ten years after the census, the Census Bureau provides the new information to states so they can make sure each district contains roughly the same number of people.

“The goal is to have a Congress, a House, that represents the population as it currently is,” Brennan Center for Justice Redistricting Counsel Yurij Rudensky said.

How does redistricting work?

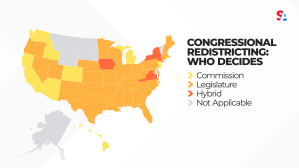

State legislatures or independent commissions redraw the maps. Both have been accused of gerrymandering, or drawing maps to give one of the political parties an advantage in elections.

“You can’t have weirdly shaped districts. They have to be compact, they have to be contiguous,” said Hans A. Von Spakovsky, a Senior Legal Fellow at the Heritage Foundation.

“Too often the lines have been drawn to try to divide voters up by race,” Spakovsky added. “I think it makes assumptions that kind of cast stereotypes.”

What are redistricting commissions?

Critics contend that bipartisan commissions aren’t as apolitical as they’re supposed to be.

“Not all commissions are created equally. There are some that are true independent commissions,” Rudensky said.

Commissions should, according to Rudensky, contain members who don’t have a personal stake in the outcome. Rudensky added there are cases where individuals serving on said commissions are hand chosen by lawmakers and party leaders, which can politicize the process.

Spakovsky agreed and said commissions that are supposed to be independent often draw maps that are equally politically lopsided.

“Whether it’s state legislators or an independent commission, you’re probably going to get some gerrymandering, but at least state legislators are accountable to voters. Commissions aren’t,” Spakovsky said.

Both Republicans and Democrats claim to be averse to gerrymandering, yet they’ve both been accused of it while in power.

“I think it goes to show how high the stakes are in redistricting, what the process does is it distributes political power,” Rudensky said. “There’s a lot of incentive for political actors and other narrow interests to try to game the system and put a finger on the scale.”

Where does redistricting currently stand?

The 2020 census revealed population growth advantageous to traditionally Republican states. Texas gained two seats in Congress while Florida, North Carolina and Montana gained one seat each. Democratic states like California, Illinois and New York are each losing a seat in Congress.

As the redrawing cycle continues, both Democratic- and Republican-controlled states are being accused of gerrymandering.

The Princeton Gerrymandering Project gave Maryland’s Draft Staff Congressional Map a failing grade, citing a signifiant Democratic advantage. In Texas, a nonprofit and 13 residents are suing the Republican Governor and Secretary of State, claiming the new map “dilutes the voting power of Texas’s Latino and Black communities.”

Many of the new maps around the country have yet to be signed into law, and legal challenges could lasts for months or even years.